Newspaper letters to the editor breathe life into the pulse of freedom.

But some of us need more action.

A local newspaper published my first byline in 1962 when I was 11 and the U.S. Supreme Court decided to remove prayer from public schools. I crafted my idea to start the school day with a moment of silence into an old-fashioned letter to the editor. Those childish words might have planted the first journalism seeds in my brain.

Now, after an untamed career of decades in local journalism, I’m back writing letters to the editor. Mike Murray, a Civitas Media executive and publisher of the Times Leader in Wilkes-Barre, PA where I worked for 17 years as a state and national award-winning news columnist, has decided my occasional guest columns are no longer welcome. Rather than embrace me as a trusted yet controversial voice in the community with something valuable to say, the publisher is treating me as just another crotchety senior citizen. Of course, letters to the editor play a crucial role in the marketplace of ideas. Citizen expression shapes civilization. Words always matter.

But my story goes deeper. My tale goes to the heart of a small newspaper’s role in any community, especially when times are tough. Local journalism shapes the spine of local truth. But bones break. Some backbones give out altogether.

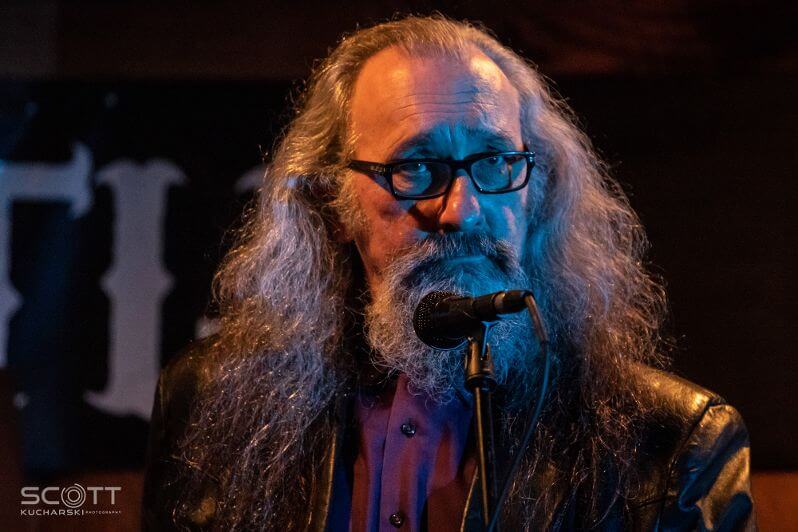

I fought my way into the business and fought to stay there. I involuntarily left the business after battling the Trump campaign for two years and getting fired three months after the 2016 presidential election. I called myself an “outlaw journalist” for about 40 years. I got fired from my first journalism job. I got fired from my last journalism job. I left undefeated.

Now 68, living in Scranton and writing psychological thrillers as an “outlaw novelist,” my first novel, “Blood Red Syrah,” features a renegade newspaper columnist who squares off against the bad faith of the business. He resents corporate duplicity. He rejects the fearful nature he sees in the eyes of advertising sales representatives. My book is not kind to America’s local newspaper business with good reason.

But when colleagues at my old paper recently called and asked for help, I locked and loaded my keyboard. Like a retired gunfighter in a spaghetti Western, at first I resisted. Then I thought better of responding with my well-honed aggression and dug deep into my gut to help.

Over the decades I matured in newsrooms good and bad, learning how, if we are to survive with honor, we must face critics who truly see us as enemies of the people. To do that, we must refuse to cave in to their attacks. Local journalists in search of truth need to aggressively fight the system more than ever. Even without working in a newsroom, I’ll be a newsman until the day I die.

But the O.K. Corral isn’t what it used to be.

All over America some local news executives are, indeed, enemies of the people – enemies of the people working hard in frontline newsrooms and guerrilla word fighters like me who still burn with the independent search for truth.

My reputation in Northeastern Pennsylvania and elsewhere is to stand up at all cost for the First Amendment. My former Times Leader bosses and I even got charged with felonies back in 1990 when Luzerne County police arrested us for doing journalism in America. When the ink cleared and prosecutors dropped the charges, the Scripps Howard Foundation awarded us a national award for our “outstanding service to the cause of a free press.”

Almost 30 years later, the First Amendment is still under attack in Pennsylvania hard coal country – this time from within.

Not long ago Wilkes-Barre city officials erected a bicentennial monument on Public Square emblazoned with the names of organizations and people who paid $35 for an engraved plaque on a brick in the cement column. One of those bricks bore the name of “The True Knights of the Invisible Empire,” a Ku Klux Klan-related group that recruited in the area about three years ago. Back then I invited the Klan leader to talk with me on my news radio program. I learned from the interview just how much work we must do to head off a continuing barrage of bigotry. The Klansman’s words alerted my listeners to a tough reality we must face together if we ever hope for democracy to prevail.

Why allow him on the show? So I could give people more information and power in their fight to survive in a cruel world.

Enter Gene Stilp, a buddy of mine, longtime national environmental activist and trained lawyer, a native coal cracker who threatened to show up in the city of his birth with a hammer and chisel and erase the “hate speech” he refused to let defame or define the good people of his community.

He and I go way back. In 2017, the same year I ended my media career, I held one end of a two-sided Confederate/Nazi flag he legally set on fire at the Luzerne County courthouse to show distain for these symbols of hatred. This time, we found ourselves on different sides of a bitter civil rights divide.

I saw First Amendment written all over the plaque debate. Gene saw a crossroads for his city and decided to take an activist path that called for censorship and destruction of public property. City police charged Gene with disorderly conduct when he climbed to the top of the monument and moved to attack the brick.

A surprising number of people, including at least two city council members and a significant number of millennials and self-styled hipsters, agreed with this 69-year-old activist who still leads hikes across Colorado’s Grand Canyon floor. Gene and his side sadly accused those of us who knew that hate speech is protected speech of supporting racism.

When the Times Leader news editor called me on the phone, he said people wanted to read my perspective on the controversy. I agreed to write a guest column for the Sunday paper, something I had periodically done for the paper over a decade on the radio after returning from a five-year stint writing news columns in California. When I came home, I wrote the Times Leader columns for free. I figured I’d write this one for free, as well.

When I finished the column, I called the executive editor whom I’ve known as a friend and colleague for about 30 years, talked about the brittle nature of the issue and agreed to meet for beers one day soon. We were excited we were all in this together.

Bad vibes electrified my brain when the column failed to show up online by 12:30 a.m., Sunday morning. Like the brown acid at Woodstock, a blurry vision of freedom clouded my mind. I immediately thought of publisher Murray, a salesman and not my kind of newspaper executive, who represented the sheepishness that too often defines local journalism. This is the same guy who caused me to stop writing my occasional free news columns.

Last year I agreed to write five special columns for the Times Leader. Laurie Merritt, a much-loved and well-respected Wilkes-Barre woman, died under mysterious circumstances in an attic fire. Police seemed to lose interest in the investigation. A specialist at covering crime, particularly homicide, I wanted to do what I do best. I wanted to call attention to facts and draw conclusions based on evidence. I wanted to raise public awareness.

I needed some red hot journalism.

After three columns the trail heated up. The district attorney expressed renewed interest. People stopped me in the supermarket to talk about the case. The now chief of police put aside our past political differences. The victim’s family felt hopeful. Like the old days, I was back to tracking a killer. Then, after holding my fourth column for more than a month without explanation, Murray abruptly stopped the series. I went back to Laurie Merritt’s family and apologized for raising their expectations. The publisher never told me why he spiked my columns. Nobody else did, either.

Late Saturday night the news editor emailed that Murray decided my free speech column would not run as a guest column but as a letter to the editor in the same space where a recent protect-the-feral-cats letter ran. The next day I sent the news editor an email asking a question I wasn’t used to asking.

“When will The Times Leader publish my letter to the editor?”

Tomorrow, he replied. Later that day, the executive editor sent me an email. The day after tomorrow, he wrote. My column, I mean letter, a powerful commentary, appeared Wednesday in its entirety.

I planned to email Murray and ask for a meeting. At the very least he should tell me why I got demoted. Was it my guest column last year about the chauvinistic political and business Friendly Sons of St. Patrick powerbrokers banning women from their bigoted annual dinner? Was it that fourth guest column about Laurie Merritt detailing evidence against the suspect and my promise to hunt him down for a fifth column? Or was it Murray’s general timidity as a stodgy non-journalist publisher/salesman?

If Murray agreed to meet, though, I worried our talk might make matters worse for those who remain in his newsroom as full-time journalists, men and women who work hard and commit their lives to fighting for truth the best they can under dire circumstances.

We stood at a crossroads.

At a recent Wilkes-Barre City Council meeting, Councilwoman Beth Gilbert said, “I hope that after further research we are able to confidently take the brick down and in the meantime, I hope that someone, quite honestly destroys it.”

Elected public official Gilbert laughed.

“I think that that could be the best thing that could happen in the city if that brick is destroyed,” she said.

Times Leader reporter Jerry Lynott wrote that Gilbert later acknowledged destroying public property was not the responsible way to resolve the controversial issue, but it was the morally right thing to do.

“I think it would be a blessing in disguise,” Gilbert said.

A few days later, outgoing city Mayor Tony George ordered the whole monument, Klan brick and all, to come down. Burn the village to save it. Fanatics expect the same fate for the First Amendment.

I doubt I’ll write another letter to the editor. And I have no reason to believe Murray will allow me another guest column on any issue. All I can hope is working journalists take my story to heart and commit to doing aggressive work on a local level whenever and however they can for as long as they can.

The day might come when proponents of free expression might not be welcome in the newsroom anymore. Corporate media shareholders might not even want your letters to the editor unless you’re a serious champion of feral cats.

Nothing wrong with that, of course.

Wild animals have rights, too.